![[Cherokee County map]](../pics/cherokee.gif) Cherokee

County, Alabama

Cherokee

County, Alabama

ALGenWeb : County Index : Cherokee County home

Desoto's Route -- A Sampling of Scholarship and Opinion

By Travis Hardin, 2006. Taken up again and completed February 2020. Last revised 2 April 2020.The author is an amateur historian and genealogist. He requests that you don't quote him. Instead, quote the professionals and journals he refers to.

UPDATE 15 Nov 2021. Dumas and team of the University of West Alabama have found 52 pieces of 16th century metal in a location in Marengo County, Alabama, east of the Tombigbee, showing Mabila territory to have been there, but not yet pinpointing the site of the battle. ( AL.com article Nov 14-15, 2021)

Around 2005 a Cherokee County woman asked me, "What can you tell me about the origin of the name 'Costa', an Indian village mentioned by DeSoto and applied to the Cedar Bluff High School yearbook? Was Cedar Bluff the site of Costa?" Costa or Coste was mentioned, along with many other chiefdoms, towns, and villages, in the journals of DeSoto's journey through the Florida territory from 1539 to 1543. The association of a modern town with any of those ancient sites could give it distinction.

That association is exactly what was attempted in Cherokee County,

Alabama in 1949 when it was decided to name the high school yearbook

"Costa" after that ancient Indian town. It happened this way: A student

at Cedar Bluff High School, the editor of the first school yearbook in

1948-49, Sue

Ingram Young (who still lives in Cedar Bluff), tells me her staff

decided to name the yearbook "Costa." They found the authority for the

location of the village in Alabama history textbooks, which quoted "The

History of Alabama," written in 1851 by Alabamian Albert James Pickett.

Mrs. Frank Stewart, a prolific local genealogist of the 1950s and

amateur historian, also quoted Pickett. Pickett in turn credited French

and Spanish maps of the 1600's, three of the four known journals of the

DeSoto expedition, and oral history from ancient Indians then living.

Pickett placed Costa on the west side of the Coosa River just inside

Alabama.

Has later scholarship improved on Pickett? Yes, and we will discuss

newer interpretations to more accurately locate several Indian towns,

including Costa, on a modern map.

First a look at Pickett's shortcomings.

In my investigation I reviewed parts of Pickett's history (which has

been improved with the application of new information). I reviewed some

of the four journals; the maps of the 1600's; and modern scholarship on

the subject. I'll show DeSoto's likely route according to the latest

scholarship in "Coosa -- The Rise and Fall of a Southeastern

Mississippian Chiefdom" by Marvin T. Smith, 2000: University Press of

Florida.

Outline Timeline notes.txt

- The DeSoto journals

- Pickett's History of Alabama , 1851

- DeSoto path, Professional opinion, 1857-1939

- DeSoto path, Professional opinion, 1980-2006

- David Sloan, The Expedition of Hernando de Soto: A Post-Mortem Report. the Arkansas History Quarterly, Spring 1992.

- " Beneath These Waters", Archeological and

Historical Studies of 11,500 Years Along the Savannah River by Kane,

Sharon; Keeton, Richard, 1993 and David G. Anderson's PhD dissertation

map c. 1993.

- Coosa: The Rise and Fall of a Southeastern

Mississippian Chiefdom, Marvin T. Smith, 2000

- The Desoto Chronicles, vols. 1 and 2, by Clayton, Knight and Moore, Editors, The 1216 pages contain the English text of three of the DeSoto journals.

- Some 1540 places and their modern locations

- The arrowhead collectors of the 1960s

- Conclusion

1. The DeSoto Journals

The DeSoto Expedition journals in English are contained in the 1993 book " The De SotoChronicles," which may be taken as the definitive English text, except that "The Inca" is not included. The Chronicles employ anthropology and archaeology.A Gentleman of Elvas at American Journeys (1904, Buckingham Smith, translator)

Biedma, at American Journeys (1904, Buckingham Smith, translator)

Ranjel at American Journeys (1904, Buckingham Smith, translator)

The Florida of The Inca -- This book is hard to find.

Conquistador and Adelantado Hernando DeSoto (also de Soto or Soto) sailed into Tampa Bay in 1539 to explore the Florida territory. Soon his army set off: 620 men with 223 horses (according to Biedma) and a herd of pigs for food. (The escaped black Iberian pigs interbred with Eurasian wild boar brought into the U.S. for hunting in the 1890s and 1930s to become today's feral hog, also called wild boar and razorback.) DeSoto's purpose was to find rumored valuables (something like the silver mines he took from in Peru), and to judge the suitability of the inhabitants as workers under future Spanish agricultural overlords. The additional goal of converting the inhabitants to Christianity was seen as a ruse by diary keepers within the party after they had witnessed captivity after captivity and slaughter after slaughter. Journals were kept, and from them -- and from interviews -- four books were written after the adventure. Some contain exact dates and the names of Indian chiefs, tribes, federations, and towns.

The Four Journals in Brief

One chronicler was Rodrigo Ranjel, the personal secretary of DeSoto He titled his book "Account of the Northern Conquest and Discovery of Hernando de Soto." In the form of a diary with near-daily entries, his version is considered most accurate. It was the last to be published, in Spanish in 1851 and in English in 1904, 1905, and 1922. The manuscript was lost but all the substance of it except the concluding chapters is preserved in the manuscript of the historian Oviedo, whose work "Historia General y Natural de las Indias" was first published in a complete form in Madrid in 1851, according to the U. S. De Soto Expedition Commission of 1939.

A second, the account of Biedma, "Relations of the Islands of Florida" appeared early, in 1544 in Spanish, but not until 1841 in French, and in English not until 1866, 1904, 1905, and 1922. Biedma was a miser of words. His was the shortest of the journals and also the only primary source.

A third, "The Account by a Gentleman from Elvas" was written by a Portuguese soldier in the DeSoto party. The Elvas narrative appeared nearly half a century before any other account of the expedition, and was the first book to be translated into English. It first appeared in Portuguese in 1557. The first English version came in 1609, early enough for a Jamestown colonist to hear of it and comment that it may be useful for the English enterprise in the new world. There have been nearly a dozen English translations from 1609 to 1933. "The DeSoto Chronicles" present a new English translation.

Fourth, Garcelaso de la Vega, El Inca, titled his account "La Florida del Inca." It "has little claim to be a primary source, other than the author's assertion that he learned his material from a survivor of the expedition. It was written in Spain over a period from the 1560s to 1589 ... The lengthy work was published in Spain in 1605." ("The Search for Mabila," 2009, ed. Vernon James Knight.)

Three of the 16th century journals, but not that of Garcelaso de la Vega, El Inca, are published in the two-volume 1994 book called The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando De Soto to North America 1539-1543 (books.google.com), edited by Lawrence A. Clayton, Vernon James Knight, Jr., Edward C. Moore, University of Alabama Press. These volumes may be bought or borrowed, for example from Archive.org.

Pickett's History of Alabama , 1851

|

Pickett's Inaccuracies

Pickett said in his January 1851 book, "I have procured from

England and France three journals of De Soto's expedition." But the

Ranjel account, regarded as the most accurate, was not published in

Spanish until 1851, nor in English until 1904.(Clayton, et.al. Vol 1,

Introduction before p. 251).

Maps of the

1600's were crude. In his introduction, Pickett said, "My

library contains many old Spanish and French maps, with the towns

through which De Soto passed correctly laid down." He places one town,

Cosa (or Coosa), at present day Childersburg, Alabama.

The US National Archives Map Collection (search "United States--Florida")

The Hargrett Rare Map Collection at the University of Georgia

David Rumsey Map Collection

The French and Spanish maps of the 1500's and 1600's, The US National Archives Map Collection,The Hargrett Rare Map Collection at the University of Georgia, and the David Rumsey Map Collection it is true, appears to show Coça on the Coosa river -- at least on a river flowing southwest. But a closer look at maps of the 1600's suggest that explorers and map makers knew only of Pensacola Bay, which they made the only bay on the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico; they imagined that four or five rivers, including the Mississippi (Río del Espiritu Santo) flowed into it, which the maps call Bahía del Espiritu Santo. Neither Mobile bay, the actual mouth of the Mississippi, Lake Ponchartrain, nor Galveston Bay are shown--only one bay is shown between the Rio Grande and Apalachee Bay.

The bay shown may have been a yet unseen one into which map makers believed all the major rivers of North America flowed. But Pensacola Bay is repeated with uncanny resemblance on this 1703 French map at the Hargrett collection (identified as Map 1703 D4, Delisle) to which Mobile Bay and the Mississippi had been added. It is my unique opinion that the single bay represents Pensacola Bay, called Achuse by Paul E. Hoffman, who sees the single bay as a merge by the map makers of a Louisiana bay called Bay of the Holy Spirit by Alvarez de Pineda with DeSoto-Moscoso's River of the Holy Spirit, the Mississippi. (Clayton, et.al. 1994, intro. p. 10.) In any case, the pre-1680 map makers were careless with the placement of bays; therefore plots of the rivers flowing into them, including the Alabama and Coosa, were also estimates.

The maps of the 1600's, viewable at the above digital libraries, show the villages DeSoto encountered. But are they accurate? Hardly. From today's perspective, the maps were gross approximations. The map makers, you can see, read Garcilaso and Elvas and then dropped some of their village on the map. Where Garcilaso had misplaced town names, with a few appeared twice (see "Indian Proper Names in the Narrative"), the map makers actually duplicated the villages somewhere else on the map. Here's a good example, a 1680 map in Spanish and Latin identified as Visscher 1680. Most of the towns mentioned by the two writers can be found, but on the map the Appalachian Mountains run east and west, and Coosa appears twice -- as Coza on the Cañoneral River flowing southwest through Alabama into the Bahía Espiritu Santo, and an eastern Cosa, appearing to be a misnamed Ocuti.

Pickett, who did not have Ranjel, still had Elvas who had written, "The governor set out from Xuala for Guaxule, crossing over very rough and lofty mountains." Yet Pickett mentioned neither the mountains nor the towns. Modern scholars plot Xuala in a "beautiful valley" in North Carolina in view of the Great Smoky Mountains to the west.

As for Coste, or Acoste (Pickett's Costa), Garcilaso said it was on the downstream end of an island 5 leagues (13 miles) long, an island surrounded by a strong flow (Ranjel). Coste was encountered only a few days after Chiaha -- a place said to be in mountains too high to travel. Coste is thought by modern scholars to be Bussell Island at the junction of the Tennessee and Little Tennessee rivers in Watts Bar Lake at Lenoir City. (Smith, Marvin T., Coosa: The Rise and Fall of a Southeastern Mississippian Chiefdom , University Press of Florida, 2000.)

Travel times don't

fit. The rate of travel for the expedition has been estimated at

17 miles per day in the open, with "double time" speeds up to 30 miles.

( Beneath

These Waters , by Kane,

Keeton, and Jameson, chapter 10.) Swanton (below) calculated 12 miles

per day. (Clayton, et.al., introduction p. 7.) Through populated areas

their pace was more leisurely.

Migrations not considered. Pickett says in his introduction, "In relation to the invasion of Alabama by De Soto, which is related in the first chapter of this work, I have derived much information in regard to the route of that earliest discoverer from statements of General McGillivray, a Creek of mixed blood, who ruled this country with eminent ability from 1776 to 1793. I have perused the manuscript history of the Creeks by Stiggins, a half-breed, who also received some particulars of the route of De Soto during his boyhood from the lips of the oldest Indians. My library contains many old Spanish and French maps, with the towns through which De Soto passed correctly laid down. The sites of many of these are familiar to the present population." George Stiggins was born 1788. (Among the Creeks). Stiggins wrote over 250 years after DeSoto, and Pickett's distance was 300 years. Oral history can survive, but a lot can be altered in 250 years. No Creek living in 1820 could have been born before 1720. How could he relate reliable information about happenings 180 years before his birth? Memorization of oral stories was the technique, but after more than a few generations the memorizations would grow foggy. The long period of time between the Indians' contact with DeSoto and the arrival of the English in the 1700' is the source of a major oversight in Pickett's thinking. Indian migrations and epidemics occurred during that undocumented period. Pickett puts the town of Coosa at present-day Childersburg, Alabama. There was a Coosa there in the 1700's, but the Coosa, or Coça, encountered by DeSoto 200 years before was in north Georgia at the Little Egypt archaeological site on the Coosawattee River, according to Smith's modern analysis.

DeSoto path, Professional opinion, 1857-1939

Schoolcraft 1857

Henry

Rowe Schoolcraft, Indian agent, explorer, and prolific writer, was

charged by the U.S. Congress to write on Indian history and ethnology.

Six volumes in two parts were published by Congress titled "History,

Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes." In it, Schoolcraft

traced the route taken by Hernando DeSoto as best he could ascertain

it.

Henry

Rowe Schoolcraft, Indian agent, explorer, and prolific writer, was

charged by the U.S. Congress to write on Indian history and ethnology.

Six volumes in two parts were published by Congress titled "History,

Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes." In it, Schoolcraft

traced the route taken by Hernando DeSoto as best he could ascertain

it.

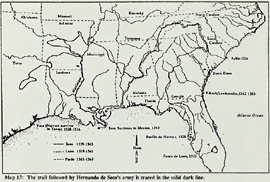

The map at right appeared in his Volume 3, page 50, Plate 44. Click

for a large JPG image.

Was there an Indian town call Costa in Cherokee County? Toward

answering that question, you can note that the path of DeSoto was

plotted on the west bank of the Coosa by Schoolcraft. Later scholarship

obsoletes some of the Schoolcraft map. As with Pickett, he places

DeSoto within Georgia and Alabama and no further north than that. I

present this map not as a definitive work but as a link in the chain

leading to better clarity. On Indian customs and language, Schoolcraft

excels.

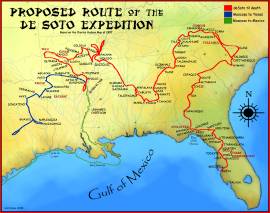

U. S. De Soto Expedition Commission of 1939. Swanton

1939 "The Report of the DeSoto Commission, U. S, Congress, House,

Final Report of the U.S. DeSoto Expedition Commission, 76 Congress, 1st

Session, 1939. House Executive Document No. 91 which was chaired by

John R. Swanton.

The Swanton reconstruction of the route in the trans-Mississippi area

was not obtained for this website. The proposed route was reproduced

from John R. Swanton, Final Report of the United States De Soto

Expedition Commission (1939: Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1985). page 343b, printed by the Smithsonian Institution Press.

The Smithsonian printing can be found on the used book market, such as

AbeBooks.

Comment by this website author: The base map used was the 1755 Mitchell

Map. It was distorted by modern standards and even if it was whole and

in readable form (which it is not), tracing a route on a distorted 1755

map makes no sense. The goal of the Commission was to identify and mark

a path on the ground for a proposed DeSoto Trail. That never happened

due to disagreement over the DeSoto route.

DeSoto path, Professional opinion, 1980-2006

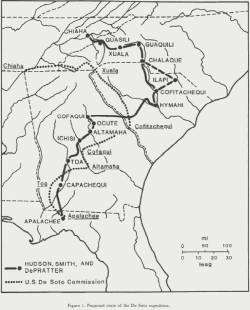

1987, Hudson, Smith, and DePratter

|

| Select this graphic to open a

large PDF of the DeSoto path through Georgia and the Carolinas, from

Tallessee to Chiaha according to Hudson, Smith, and DePratter. |

See at Scholar Commons, 1987, The Hernando De Soto Expedition: From Apalachee to Chiaha, where they explain their proposed route is more accurate than the 1939 study. On page 6 of that booklet they map their route through Georgia and the Carolinas along with the corresponding 1939 route. Hudson, Smith, and DePratter are among the first to break from the Pickett constriction and show a path considerably north of the 1939 path.

1998, Charles M. Hudson, "Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun."

|

David Sloan, The Expedition of Hernando de Soto: A Post-Mortem Report. The Arkansas Historical Quarterely, Spring 1992

Sloan part 1

(.doc)

Beneath These Waters, 1993.

The copy

at Archives.org

Previous to the construction of the Richard B. Russell dam on the

Savannah River, experts studied prehistoric and historic sites for the

Corps of Engineers and the National Parks Service who supervised the

study. It was published, aimed at the general public, as "Beneath These

Waters: Archaeological and Historical Studies of 11,500 Years Along the

Savannah River," and written by Sharyn Kane and Richard Keeton.

Desoto's Trail on page 133 was provided by David G. Anderson from his

Ph.D. dissertation. Anderson's map also shows the forays of two

subsequent Spanish explorers, Luna and Pardo.

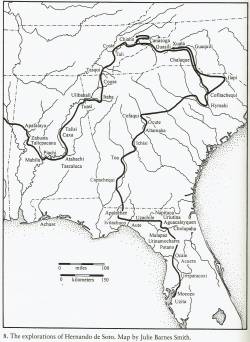

Marvin T. Smith, 2000

Marvin T.

Smith, Coosa: The Rise and Fall of a

Southeastern Mississippian Chiefdom.

Marvin T.

Smith, Coosa: The Rise and Fall of a

Southeastern Mississippian Chiefdom.

After co-authoring previous books examining Southeastern native Amerians, Marvin T. Smith writes his own. As an archeologist he studied the southeast prehistoric peoples, specifically the Coosa paramount chiefdom and the Coosa people. Their world was turned upside down by the arrival of De Soto, and Smith makes a study of the Spanish passage as well as the anthropology of the native peoples, tying archaeology to the journals of the De Soto expedition, and producing a studied map of the likely path of De Soto. At left is the map from Alabama eastward from page 36 of "Coosa," drawn by Julie Smith, and used with her permission. The Smith path agrees closely with the Hudson path.The book can be bought at AbeBooks and similar online book sellers. As with the other illustrations, click on the map to reveal a magnified map.

The DeSoto Chronicles

Lawrence A. Clayton, Vernon James Knight, Jr. and Edward C. Moore, Editors.University of Alabama Press, 1993. 1216 pages.

Where to find The De Soto Chronicles:

It may be borrowed from the Internet Archive.

Excerpts can be viewed here at Google.

Buy by looking it up at Google Books. The University of Alabama will print a copy on order.

The De Soto expedition was the first major encounter of Europeans with North American Indians in the eastern half of the United States. De Soto and his army of over 600 men, including 200 cavalry, spent four years traveling through what is now Florida, Georgia, Alabama, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. For anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians the surviving De Soto chronicles are valued for the unique ethnological information they contain. These documents, available here in a two volume set, are the only detailed eyewitness records of the most advanced native civilization in North America, the Mississippian culture, a culture that vanished in the wake of European contact.

Three of the journals are found here in new English translation: Biedma and Rangel are translated by John E. Worth; the Gentleman of Elvas by James Alexander Robertson. The Cañete fragment is included. The thick book by Garcelaso de la Vega, "La Florida del Inca," is NOT included. The Chronicles has a 700-book bibliography of DeSoto studies and a list of Indian proper names found in the journals.

Take The DeSoto Chronicles and add to it the publications by Charles M. Hudson ( Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun) and Marvin T. Smith ( Coosa: The Rise and Fall of a Southeastern Mississippian Chiefdom ) and you have a canon of modern research.

On Archaeological Research and Spanish Bells

The caption of a picture of a bell:

A "Clarksdale" Bell. Small spherical bells made of sheet brass were used by Spanish explorers as gifts to native chiefs during the sixteenth century. This specimen was excavated from a Native American village in the Southeastern United States. Archaeologists have given this distinctive type of bell the name 'Clarksdale', after a site near Clarksdale, Mississippi ... Such finds may be used as evidence in the search for the route of De Soto's army." - Chronicles, Vol. I, p. 287.

Some 1540 places and their modern locations

Chiaha is believed located on Zimmerman's Island in the French Broad River. Smith p. 35 quoting Hudson, et al. 1985.Coste -- The main town of Coste is believed to have been on Bussell Island at the junction of the Tennessee and Little Tennessee rivers (Smith p. 35). Garcilaso said it was on the downstream end of an island 5 leagues (13 miles) long, an island surrounded by a strong flow (Ranjel). Where two rivers meet would produce a strong flow.

Tali -- Up the Little Tennessee River (Smith p. 35)

Tallimuchasi -- near Fairmont, Georgia. (Smith p. 37)

Coosa -- Little Egypt archeological site on the Coosawattee River. (Smith p. 35.) The Coosa people migrated south every third of a century and were at Childersburg, Alabama by the 1700s (Smith, p. 119).

Itaba -- The Etowah River archaeological site.

Ulibahali and Apica -- These two towns, which had abundant muscatel grapes (muscadines) in early September (Julian calendar) are shown on the Georgia-Alabama line by Smith and Hudson. Tusai as well was there on the Coosa.

"A pretty town hard by the river" (Rangel) beyond Ulibahali was mentioned by one journalist and might be a village in present Cherokee County's Alexis community, since the army supposedly kept to the south bank. Or it could have been in the Rome cluster. Several village sites have been located by archaeologists along the Coosa between the state line and modern Coosa, Georgia. (Smith p. 86).

Talise -- Childersburg, Alabama

Mabila -- a fortress town, site of a hard-fought battle. Most writers put it at the confluence of the Alabama and Cahaba Rivers 9 miles south of Selma, some further north.

UPDATE 15 Nov 2021. Dumas and team of the University of West Alabama have found 52 pieces of 16th century metal in a location in Marengo County, Alabama, east of the Tombigbee, showing Mabila territory to have been there, but not yet pinpointing the site of the battle. ( AL.com article Nov 14-15, 2021)

The Arrowhead Collectors of the 1960s

In 1964 I returned from my Air Force service to Cherokee County and lived for a while with my in laws, the Roy Lambert household, in the vicinity of Alexis, Alabama. The dam was in place, the Weiss Lake bottom had been cleared by 1960 and the water had risen to its level by 1964. Roy Lanbert and his boys were joined by many others in the new hobby of locating artifacts -- mostly arrowheads -- uncovered by the action of water, and mounting the well-formed ones in frames with glass fronts and foam backing to display. Thousands of arrowheads were collected over several decades by hundreds of people. The numbers of arrowheads (both well-shaped and broken or malformed) in the first two feet of soil tell of a virtual Indian metropolis on the banks of the Coosa. * Is there a way to learn something from those loose artifacts picked up at random? Few of the items were located "in place" as an archaeologist might say. Nevertheless if there is a Cherokee County collector from those days who can produce some photos of and identify the arrowheads in some useful way, I would like to put your story on this Web site.*Anything on the ground surface left alone for long enough will sink down 10 to 30 cm beneath an accumulation of earthworm casts, an observation based in Charles Darwin's The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms with Observations on their Habits, Chapter 3.

Conclusion

Most studies put DeSoto's path on the southeast side of the Coosa River, and that is strike one against Cedar Bluff, which is on the north bank. And Cedar Bluff is not Costa. Recent revisions put Costa on Bussell Island on the Tennessee River in mid-Tennessee. We need to abandon Albert James Pickett's idea that Costa lay on a river in Cherokee County. As late as the 1950s textbook authors cited Pickett, and Pickett's Alabama-cetric view of DeSoto's trail was still taught in Alabama schools. If you want to maintain Pickett's tradition, that's fine. It would be a shame to suggest abandoning a good yearbook title that's worked for 70 years. Since when does tradition have to be true? I like Ranjel's description of "A pretty town hard by the river" with abundant muscadines in the fall as an ideal Cedar Bluff.A Note About the Cherokee

"It is of interest that the Cherokee, who populated eastern Tennessee and northwest Georgia in the eighteenth century, were newcomers to the area. The early Spanish accounts leave little doubt that the people of the paramont chiefdom of Coosa were all speakers of the Muskogean language family.

-Smith, "Coosa," p. 49

To Cherokee County Home

To top

To outline