Births

Book Store

Cemeteries

Census

Churches

Court Records

Deaths

Ethnic Interests

Family Connections

Research Guide

History

Land and Mapping

Libraries

Links

Lookups

Marriages

Military

Newspapers

Order Records

Queries

Researchers

Surname Register

Tax Records

Tips for Research

Towns

About This Site

A History of the “Irwin Invincibles” or the “Henry Light Infantry”

Source: Steven Parrish, Commander, SCV, Henry Light Infantry Camp #1968

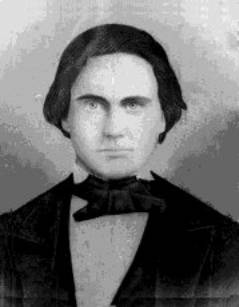

James Whiddon

In December 1861 the War of the Rebellion was at hand. A Company of soldiers from Henry County, Alabama known as the “Irwin Invincibiles” later the “Henry Light Infantry” was organized by J.L Irwin. He owned a portion of what was once a large plantation near Shorterville, Alabama. He had been commissioned a Captain in the Confederate Army. J.L. Irwin’s influence was largely due to his uncle, Major General William Irwin, a great Indian fighter. General Irwin’s empire at one time encompassed some 500,000 acres.

The town of Franklin, Alabama was the rally point where many volunteers from the surrounding area signed up for service. Franklin Landing, as they called it, was established in the early part of the nineteenth century and lay on the bank of the Chattahoochee River. It borders Georgia near Fort Gaines. Franklin is no longer a town. All that remains of the town after the great flood of 1888 is a marker, "Franklin” on the side of the road near the River.

One of these volunteers was my Great, Great Grandfather, Private James Whiddon. Born in Henry County on November 28th 1842, fate would have it that James would be the ideal age to fight in the bloodiest war ever waged on American soil. His father William, was a slave owner as was his uncle Lott. Farming was the way of life for all southerners, and though many farmers did not own slaves, slavery was a part of farming. Be it considered right or wrong, it was acceptable at the time.

As tensions heated up between the northern states and the southern, several issues would bring about the beginning of the conflict. Many scholars argue the causes of the war trying to determine “a” cause for it. I am certainly no scholar nor an expert on the War itself. I do rather tend to value and agree with the explanations of those that lived and fought during that era. One such individual was Major General John B. Gordon. Gordon, whose name will appear many times in this work, was a general officer for the Confederacy. He was a commander in the 2nd Corps. Following the war, he was elected the Governor for the State of Georgia for four consecutive terms.

The simple fact is that there were many causes and slavery was, as Gordon would later describe,

“one of the tallest pine in the political forest.” Of slavery he would say, “neither its destruction on the one hand, nor its defense on the other, was the energizing force that held contending armies to four years of bloody work.” He said, “if summoned to the witness stand every Union soldier would testify that the cause was preservation of the American Union and not destruction of Southern slavery.” "As for the South,” he says, “it is enough to say that perhaps eighty per cent of her armies were neither slave-holders, nor had the remotest interest in the institution.” He continues his comments by writing, “…the South could have saved slavery by simply laying down its arms and returning to the Union.”

James Whiddon enlisted with the Confederate Army on August 8, 1861 at the age of 18 years. One need understand that because re-assignment was commonplace during this four-year war, many of those soldiers who signed with J. L. Irwin did not necessarily follow the same path Whiddon did. This “path”, however is one that led him, and others from around Henry County to the near brink of their destruction. For sake of posterity, this overview is written in the context in which he served during the War, and it goes without saying—he and his comrades certainly saw some of the heaviest action of that time.

The Irwin Invincibles were successively designated 3rd Company E 25th Georgia Infantry Regiment. There are two principle possibilities why this group, mustered in Alabama would be attached to a Georgia regiment. First, Franklin was on the border of Georgia and probably was closer to an active regiment there. Secondly, perhaps these soldiers or their extended families were from Georgia or had close ties there. At any rate, by the 18th of September 1861, the regiment was in White Sulpher Springs in what is now West Virginia performing picket duties. They had been dispatched from there to Georgia by the Secretary of War. Once they arrived in Georgia, they set up camp on Jan 12, 1862 near Savannah. For the next four months they did as most of the other companies did around that time—prepared to fight.

They celebrated camp life with the stories they heard about Johnston’s great victory at first Manassas, and the horrors that they thought could never be equaled at Shiloh. They themselves would surpass witnessing such horrors by the fall of that same year.

As Spring blossomed in 1862, Private Whiddon’s enlistment had been “extended” for two years and he received a $50 bounty on March 1st for that extension. Company E of the 25th Georgia was transferred to the 38th Georgia Infantry Regiment Company “I” on May 2nd 1862 at Thunderbolt, Georgia. This would place them in the 2nd Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia under General Thomas J. Jackson, Ewell’s Division, Lawton’s Brigade. The army moved northward to Virginia, and readied for a fight. They wouldn’t have long to wait.

In May of 1862 General Johnston was skirmishing with McClellan’s Federals north of Richmond. On the 31st he undertook a series of movements designed to attack two exposed Union divisions located between Fair Oaks and Seven Pines. He had quite a bit of success until the corps he was attacking managed to make it across the Chickahominy River. An interesting event took place on that day which would change future events for the Confederacy.

General Joseph Johnston, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, was watching the fight unfold from a knoll some 200 yards north of Fair Oaks Station. He was chiding a nervous staff officer who was ducking as bullets hummed by. “Colonel,” said Johnston,

“there’s no use of dodgin’, when you hear them they’ve passed.”

Just about that time, a bullet struck Johnston in the shoulder followed immediately by a shell exploding nearby and a fragment from it going into his chest. General Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia—the event which unknown at the time would change the War entirely.

The 38th Georgia participated in the Seven Days Battles at Gaines’ Mill on June 27, 1862 where losses were heavy. This was the third day of the “seven” and the Federal V corps had established a stronghold north of the Chickahaminy River. Throughout the day the Union Army had repelled numerous assaults by Confederates. Finally, near dusk the Rebels mounted a coordinated attack that drove the Union forces back toward the river. The Thirty-eighth was singled out for there gallantry in a report from Brigadier General Alexander R. Lawton on the fight at Seven Days.

“…after the Brigade was fairly engaged, the two regiments on the left (Thirty-first and Thirty-eighth Georgia) were beyond my reach and under the immediate direction of my adjutant-general…in emerging from the wood(s) these two regiments found themselves in the hottest part of the field, where our friends were pressing on the enemy toward the left, and joined them in the contest at that point under a murderous fire. Steadily on did they press, doing great execution until the last cartridge was expended and then joining heartily in the last charge after night-fall which resulted in the shouts of victory.”

He further said this of the Thirty-first and the Thirty-eighth Georgia:

“The conduct of these two regiments, officers and men, and of Captain E.P. Lawton, who led them, cannot be too highly appreciated, and the list of killed and wounded, for the short time they were engaged, attests to the danger which they so gallantly faced.”

The thirty-eighth lost 54 killed and 118 wounded. Among those killed was James’ brother in law who fought by his side, Crawford Hix. Crawford left behind three children, one of whom he never had seen: his daughter Margarett.

They were to fight again at the battle of Malvern Hill on July 1st 1862. This was the sixth and final day of the “Seven Days” as General Lee launched a series of disjointed assaults on the nearly impregnable Union positions on Malvern Hill. The Confederates lost 5,300 casualties that day without gaining an inch of ground. Union General McClellan would withdraw his troops back to the James River and entrench. General Lee did not pursue. After the War, General Lee would reflect on this moment in time as the one opportunity he felt he had passed up which would have given him the best opportunity to win the War. Once McClellan ceased to threaten Richmond, Lee sent Jackson to operate against Major General John Pope’s Army along the Rapidan River, thus began the Northern Virginia Campaign.

The Thirty-eighth Georgia was assigned to guarding trains at Cedar Mountain. They then fought at Rappahonnock Station on August 23 which was a prelude to the upcoming fight at 2nd Manassas.

On August 28, 1862, four federal brigades moved up the Warrenton Turnpike towards Centerville. Jackson opted to attack the unsuspecting Pope. He waited until Hatch’s Brigade passed and ordered artillery to open on Gibbon’s Brigade. Gibbons, supported by Doubleday tried to face the onslaught of the Confederate forces and formed an attack line on the Brawner Farm. Ewell unleashed two brigades (among them the 38th Georgia under Lawton) and stormed across the farm slamming into the oncoming federals driving them back. The fighting here was horrendous. At a distance of no more than 75 yards they poured volley after volley into each other’s ranks. As darkness fell the fighting continued as the men on opposing sides looked for musket flashes to determine their point of aim. The Federals retired and the Rebs were too exhausted to pursue. They fell back and covered the artillery that evening.

The next day brought a change in command. General Ewell had been severely wounded in the leg. General Lawton would command his Corps. The 38th Georgia joined others as the set up a line of defense along an unfinished railroad. Pope would go on the offensive knowing he outnumbered the Confederates greatly. The fighting was fierce on the 29th as Pope finally ordered an attack on the Confederate left. Grover and Hooker’s Divisions mounted a frontal assault directly into Lawton’s Brigade. Throughout the day, many men would retire and fall back to the stony ridges behind their lines to look for General Longstreet.

Weakened in numbers and exhausted, the first two lines of Lawton’s Brigade broke under the federal attack. The third line including the 38th Georgia held strong and offered a rallying point for the two retreating lines in front of them. The federal attack was stopped in its tracks. The next day, the 38th was moved to a wooded top of a stony ridge and held in reserve. They advanced as Longstreet arrived on the field, unknown to Pope, striking him hard on the left flank. The routed Federals fell back and tried to set up a stronghold on Henry House Hill. Jackson seeing this ordered their right flank hit hard by his troops. The two-pronged attack forced Pope to order a retreat at 8:00 p.m. on August 30th. One Union General to another: “It’s another Bull Run, sir, it’s another Bull Run!”

On September 12-15, 1862 they captured Harpers Ferry. General Jackson left A.P Hill’s division there to salvage and capture property as well as parole any prisoners. He then turned north to assist the rest of Lee’s Army in the bloodiest fighting up to that point near a small town in Maryland called, Sharpsburg. They fought on one of the bloodiest parts of the battlefield (Antietam), at a place known today as “Miller’s cornfield.” The fighting started there at dawn on the morning of the 17th. This day, the fields ran red with blood. To better understand the battle, it is important to know that there were three basic points on the battlefield that the two armies collided. The fighting in the cornfield, Dunkard Church and the “West Woods”, the fighting in “Bloody Lane” and that at Rohrbach’s (later Burnside’s) Bridge. It was equally horrific in all places the entire day prompting historians refer to this day as the “bloodiest day in American History.” Averaged out, an American was killed or wounded every two and a half seconds during an 11 hour period. General Hooker’s artillery began a murderous fire on Jackson’s men in the cornfield. The two armies collided and the Confederates gained some ground there, prompting Union General Joseph Mansfield to order a counter attack with even more reinforcements. Hooker said of Miller’s cornfield, “every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before.” In an effort to relieve some of Mansfield’s men isolated around the Church, Sedgwick’s division moved into the West Woods, just northwest of the church. They were struck from both flanks by Jackson’s men and took appalling casualties. Fighting continued on an unprecedented scale the entire day. Around 4 p.m. A.P Hill’s division arrived on the field and immediately jumped into the fight. His division struck Burnside’s and drove them to the heights near the bridge they had taken earlier. The Battle of Sharpsburg concluded leaving 23,110 Americans killed or wounded. The Regiment would fight at Boteler’s Ford on September 19 during Lee’s retreat back into the South.

Lee’s Army moved to Fredricksburg in December. On the 13th, the 38th Georgia faced General Meade on the extreme southern part of the battlefield. With General Jubal Early commanding the division, the 38th participated in a route of charging Union forces near Prospect Hill and Hamilton’s Crossing. They in turn, received heavy casualties.

After Fredricksburg, some of the 38th Georgia was re-assigned to the 60th Georgia Infantry. Private James Whiddon and some of what was left of the Henry Light Infantry were among these men. It was March 1, 1863.

Following the Battle of Fredricksburg many of Lee’s forces were maneuvering to repel General Hookers “rear attack” plans on the forces at Fredricksburg. The 60th Georgia was left behind under General Early and occupied positions on and around Marye’s Heights in the town. On May 3rd 1863, General John Sedgwick ordered a Federal assault on the city and drove the outnumbered Confederates from their positions forcing them to regroup west and southeast of town. As soon as Sedgwick’s Corp occupied the Heights, they moved on with their objective: to meet up with Hookers forces at Chancellorsville and crush Lee’s Army. Early, by this time had crossed the Rappahannock River at Bank’s Ford and set up a line of defense. General Lee detached two divisions from his lines at Chancellorsville and sent them to reinforce Early at Salem Church. Sedgwick arrived and ordered several Union assaults, which were repulsed with heavy casualties. The Confederates counterattacked and gained “some” ground. After dark, Sedgwick withdrew his forces across two pontoon bridges under harassing fire from Confederate artillery. Hearing Sedgwick had been repulsed; Hooker abandoned the campaign and recrossed the Rappahannock. The Battle of Chancellorsville was over. The cost however, was great. General Jackson had been shot by one of his own men and was relieved of his duties. General Richard S. Ewell was placed in charge in Jackson’s stead.

On June 4th General Early’s Division began marching from Hamilton’s crossing. The Division halted for 2 days at Culpeper Courthouse and proceeded to Front Royal where they arrived exhausted on June 12. General Early gave orders for General John B. Gordon to deploy his Brigade to the left of Staunton Pike leading into Winchester on June 13th and form a battleline 3 miles southwest of the town. General Gordon deployed as ordered and quickly confronted enemy skirmishers behind a brick wall. He ordered a charge of the works and this forced a Union retreat. On June 14th the fighting increased with the Federals occupying the town and a fort within it. As the Confederates continued a relentless attack of the occupying forces, they forced them from the town and down the Martinsburg Turnpike. Gordon’s Brigade had been ordered to take the fort in the town, but by the time they arrived there, it had been abandoned. He rerouted his brigade to assist, but arrived in time to only help take control of prisoners and recover horses. The Battle of 2nd Winchester had concluded.

The next great fight that this Regiment would face would occur in Adams County, Pennsylvania. A little town called---Gettysburg. The 60th Georgia’s chief participation in the Battle of Gettysburg was on July 1st, 1863. Forces fought on the part of the battlefield that would later be called “Seminary Ridge” Some of Ewell's Division would also be heavily involved on and around “Culps Hill” on July 2nd. About 3 p.m. Major General Rhodes’ Brigade was well involved in a fight against Union forces that were overwhelming the left flank of Doles’ Brigade. General Gordon’s Brigade was ordered to move up in support. As they met the retreating Brigade of Doles’ he noticed the Federals were cautious and not wanting to expose there right flank as a result of this charge. The Federals in turn began forming a new line at the crest of a hill when Gordon’s Brigade hit them with such a charge that Gordon himself said their resolve was “rarely equaled.” The enemy put up stiff resistance until their “colors” of the two lines were no more than “50 paces” apart. This essentially left the flank, which this new line was to guard, exposed. The Federals were pushed from the hill and sustained heavy losses in killed, wounded, and captured. Major General Early ordered the offensive to cease. Obviously, this was an order given to him by Ewell. One of several command decisions issued by Ewell which would cause a cloud to loom over his ability to command. Following the defeat at Gettysburg, the Army recrossed the Potomac River at Williamsport on July 14, 1863.

On April 11, 1864 these Alabama boys were reassigned from the 60th Georgia to the 61st Alabama Infantry Regiment Alabama Infantry Regiment). They were assigned to Brigadier General Cullen A. Battles’ Brigade of Rhodes’ Division of 2nd Corps under General Jubal Early and Richard Ewell. This would be the last regimental change for the once, Irwin Invincibles. From this point on, the remnants of what was left fought together till the end of the War.

A new commander of the Army of the Potomac had taken over and his method of fighting was different than those of his predecessors. General U.S. Grant had been placed in charge after Meade failed to pursue Lee’s Army into Virginia after the battle of Gettysburg. Abraham Lincoln, frustrated with all of his previous commanders, liked what he saw in Grant during the Vicksburg campaign. Grant’s objective, as stated earlier was not the same as the objectives of his predecessors. He did not focus on the capture of Richmond, but rather the destruction of Lee’s Army entirely. This was not a popular idea among the citizenry of the North as it sent many of their sons to their death. The statistics of killed and wounded increased greatly in 1864 and it was because of this philosophy Grant used in war.

Lee on the other hand knew Grant’s nature having served with him in the Mexican War. This is one of Lee’s greatest attributes: his ability to predict the method of war waged, by knowing his opponent’s traits. Lee therefore changed his methods of fighting. It is along in here that we see the introduction of “trench warfare” as the Confederates built nearly impregnable strongholds throughout the remainder of the War. This contributed to the large differences in killed, wounded and missing from that point on.

Some of the deadliest fighting was yet to come. At The Wilderness (May 5-6 1864) the 61st Alabama Infantry Regiment was among the first to engage in the fight. At 7:15 a.m. Union General Warren reported a “considerable enemy force” on the turnpike about two miles west of Wilderness Tavern. Grant and Meade, thinking it was one division only, ordered him to engage. About noon General Griffin’s division attacked the Confederates and routed General John Jones’ brigade of Virginians and then advanced against Battle’s (including the 61st) and Doles’ brigades of Rhodes’ division (south of the turnpike). During the route of Johnson’s Vriginians, General Ewell rode up hard and fast to General Gordon and said, “General Gordon, the fate of the day depends on you, sir.”

While this was going on, Battles’ brigade held off a charge and countercharged. General Gordon later would write of this part of the battle, “…the steady roll of small arms left no doubt as to the character of the conflict in our front…we hurried with quickened step toward the point of heaviest fighting. Alternate confidence and apprehension were awakened as the shouts of one army reached our ears. At one point the weird Confederate “yell” told us plainly that Ewell’s men were advancing.”

Confederate Generals Gordon and Daniels saw that a gap had been exposed in the federal lines on a union counterattack and thereby exposing the right flank of one of their lines. Gordon ordered committed forces to regroup, reform at a right angle to the line previously formed and attack on two fronts. General Ayres brigade was driven back and General Griffin was forced to pull back his entire line. The fighting on May 5th was over. The 61st sustained heavy casualties that day, but not as heavy as what they inflicted. The Regiment captured a federal artillery battery and killed union Colonel David T. Jenkins and nearly annihilated his regiment: the 146th New York Zouave. (The 146th New York was in the 5th Corps under Major General Warren; General Griffin’s Division; 1st Brigade under General Ayres.)

Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21, 1864) was the next encounter Lee and Grant were to have. Both, unknown to one another ordered their armies to the village of Spotsylvania Court House. Skirmishing and heavy fighting at times while the armies were moving into position was frequent on May the 7th to the 9th. This is largely because of Grant’s attempts to move around the Army of Northern Virginia in order to place himself between Lee and Richmond, VA. This attempt would fail as Hampton and Early (who had temporarily placed in command of 3rd Corps) held back Hancock’s Corps on the Brock Road near Todd’s tavern. 1st and 2nd Corps under Anderson and Ewell were engaged with Grant’s forces near Spotsylvania Court House on the 8th.

By May 10th Lee’s army was entrenched and held a line of battle, which was semicircular in shape with a “horse shoe” type salient at its apex. This would be referred to as “the mule shoe” and would facilitate two of the bloodiest days in American history. Ewell’s troops (61st included) held the apex of the mule shoe which would be the northern and western side. On that afternoon, Grant launched attacks on virtually all fronts of this “mule shoe”. Grant’s assault on Ewell’s Confederates drove many of them from their works.

Battle’s (61st among them) and Johnson’s brigades met General Upton’s tenacious brigade head on when they breached the salient. A terrific fight ensued and Upton’s brigade refused to give. Gordon and Walker brought up reinforcements on the flanks of the engaged Confederates and forced Upton’s Federals to retreat. In doing so, they were hacked up piecemeal by Rebel musketry and artillery. Losses for the day were great on both sides.

Among the Confederate casualties that day was Corporal Lott Whiddon, James’ uncle who had fought at his side during the entire war. Lott had enlisted in Franklin on May 10th, 1862—he died at the age of 27, two years to the day of his three-year enlistment.

Upton’s breach of the mule shoe gave General Grant an idea. On May the 12th Grant launched a full-scale attack on the salient. As pressure was placed on the outside, the fighting grew concentrated in an area on the northwest side of the mule shoe, a place which would be known to the soldiers who fought there as…”Hells Half Acre” and later as “The Bloody Angle”.

General Hancock massed a huge amount of troops in front of the Confederates shortly after midnight. Johnson’s division occupied the earthworks having been left “on guard” with only muskets and two field pieces of artillery. General Johnson noticed the troop concentration and request from General Ewell that supporting artillery be brought back up to support in the advent of attack. General Ewell, not realizing the urgency of the request, ordered the guns to be placed back at first light. Hancock attacked with a battalion, which was held off a short time by Johnson’s men. The Federals eventually engulfed the earthworks and captured Johnson and 2,800 of his men.

Overcome by their own success, the Federals prepared to continue their route of the Confederate army. General Lane’s brigade at Ewell’s right flank didn’t share their confidence. His brigade refused to run, and instead poured accurately deadly volley after volley into Hancock’s men forcing them to recoil and hold what they had.

By this time, General Lee had been aroused from his tent and proceeded dangerously close to the fighting. The men in Gordon’s brigade were rallied and attacked with force. They retook the earthworks with the exception of the trenches at the apex of the salient: The Bloody Angle.

From early morning until late afternoon a bloody struggle continued between North and South over the logs and trenches at Bloody Angle. At one point, Federal mortar batteries set up and carefully triangulated their positions and dropped deadly accurate motors on the Rebels. The soldiers on both sides would jump up, rest their gun on a log and fire into the face of their enemy. Men would thrust their bayonets through crevices in the logs. Soldiers would grab their foe and try and drag them over the logs to by killed by a comrade. The dead and dying would be flung to the rear of the works to make room for those who could still fight. The trenches filled with blood, death and suffering as the wounded became covered with the dead. Then, it started to rain. The trenches that were filled with blood now became greasy as the soldiers lost their footing. The mayhem continued for the rest of the day with much of it being hand to hand because of lack of ammunition or time to reload.

Meanwhile, Gordon was digging a defensive line south of the salient. Regrouping for another round of action. Darkness fell and the fighting ceased. Hancock withdrew his veterans from the ditch. The next morning, Lee ordered the salient evacuated and a new line of defense set up where Gordon’s men had been working all night. The carnage had subsided and neither side wanted anymore of the other. A newspaper reporter from Washington who had been covering the war took a tour of “Hells Half-Acre” on the 13th and had this to say, "God forbid that I should ever gaze upon such a sight again”.

At 6:30 on the evening of May 13th, the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House had ended. Federal casualties were 16,000 while Confederate casualties were 8,000. Seemingly a Confederate victory? It cost Lee 18% of his fighting force. He was running out of men.

Jeb Stuart’s smaller cavalry had maneuvered to get in the path of Sheidan who was advancing on Richmond while the Spotsylvania battle was in full swing. Stuart, a fighting man was worried that Sheridan would allude him and not fight. Sheridan had no intentions of running. The two foes clashed at Yellow Tavern just north of Richmond on May 11th. Stuart was shot in the side as he rallied the Confederates. The ball pierced his liver and he would die in Richmond the following day. This fight held Sheridan up until reinforcements from Richmond could arrive. Sheridan was forced to cease his efforts on the city.

The battle at the North Anna River (May 23-26,1864) was the 61st’s next fight (some accounts may not specifically mention the 59th or 61st Alabama. By this time, their ranks were getting low. At any rate, they were assigned to Battles’ Brigade possible attached with the 26th Alabama Infantry Regiment).

Following the fight at the North Anna River General Ewell would become ill and be temporarily replaced as their corps commander. Lee would make it permanent. He was to be replaced by General Jubal Early. Early would maintain command of the 2nd Corps until the end of the war.

The Union army maneuvered to northeast of town, near the old “Seven Days” battlefield and prepared to assault Richmond from the east. Sheridan seized a crossroads on a hot June day in 1864. The only point of notoriety at that crossroads was a tavern called…Cold Harbor.

Lee had positioned his army between Grant and Meade, and the city of Richmond. There was only one way the Federals were going to take Richmond—that was to go through Lee. On the evening of June 2nd the Confederates built earthen trenches capped off with logs (with gaps between them to shoot through). The next morning was to be the “bloodiest hour” of the War. Federal soldiers sewed their names into their clothing with pieces of paper so their bodies could be identified when they were killed. Everyone on that battlefield knew what the next morning would hold. Battle’s Brigade was fighting in the northern most part of the battlefield and did not receive the casualties sustained at Wilderness and Spotsylvania. The point of the main Union assault would be in the center. It would prove to be exactly what the Federal soldiers thought—a slaughter. The Federals lost between 7 and 9 thousand men in less than an hour while Confederate casualties would be around 1,500. When asked following the war what the biggest mistake he made was, General Grant replied, “Cold Harbor”. A song written later of the battle would include these words of a Rebel soldier, “…in just a half-an-hour, ten thousands Federals died, my blood ran cold to watch’em fall--I closed my eyes and fired”. How true these few words were.

Once Cold Harbor ended, most of the Army of Northern Virginia migrated to Petersburg and prepared for a long siege, which would be the last stand for the South in the war. General Early moved northward, however, at Lee’s direction. He took 2nd Corps back into the Shennandoah Valley. Monocacy or the “Battle that Saved Washington” was spearheaded by General Early’s troops on July 9th 1864.

From there, his heavily outnumbered soldiers sustained great losses at 3rd Winchester (September 22, 1864). In this battle, Early took his men and attacked union General Sheridan while he was still trying to organize his troops. The Federals held and the Confederates sustained heavy losses. Early was forced to retreat, and several days later Sheridan caught up with him and inflicted heavy damage to the corps, outnumbering them greatly at Fishers Hill.

Sheridan’s Army was encamped at Cedar Creek on October 19 when Early ordered an attack on his position. This came with overwhelming surprise and success. The Federals were driven back and forced to regroup. Then, Sheridan ordered a counter attack, which due to overwhelming forces had great success. General Early was forced to retreat and rejoin the remains of the Army of Northern Virginia at Petersburg. The south would never again pose a threat to the North in the Shenandoah Valley.

The Petersburg Siege would last until the early part of 1865. While the siege was underway, the Army of Tennessee was on its final leg. General John Bell Hood would commit one of the greatest debacles of the war. With the Federals dug in at Franklin, he ordered a charge on November 30, 1864, which made Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg look small. His army was decimated and he lost five general officers that day, among them, General Patrick R. Cleburne. The Army of Tennessee was essentially destroyed.

Battle’s brigade participated at the fight at Ft Stedman on March 25, 1865. Petersburg would be evacuated and Lee’s army would be on the move, westward, abandoning all hope of defending Richmond. Starved and with no hope of victory or surviving to achieve a political stalemate, Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9th 1865.

The 61st Alabama Infantry Regiment surrendered along with the rest of what was left of the Army of Northern Virginia. Records indicate that there were 1,082 men listed as being in this Regiment. When they surrendered under the command of Captain August B. Fanning on April 9th, there were only 27 men remaining.

James Whiddon’s last recorded entry in the National Archives (other than that of April 9, 1865) was on a Company Muster Roll for July and August 1864. The notation on the card read, Private James Whiddon was absent at the time the Company had last been paid on June 30th 1864. The reason for his absence was listed as “Absent—Wounded”. He was probably wounded at The Wilderness or Spotsylvania due to those two battles nearly annihilating the entire regiment. If I had to guess between the two, I would say Spotsylvania. Since his uncle Lott Whiddon was killed there, it is safe to assume that James was next to him when he was killed. With that thought in mind, it should be assumed that they were heavily engaged on that battlefield on May 10th. The fact that he finished the war as a Sergeant indicates that he recovered from the wounds received and fought once more.

After the war, those that survived probably took months to return home. James returned home and married Mary Hodges on June 8, 1867. They had 10 children, two of which died in their youth. He died on October 17th 1900 at the age of 57. He is buried in the cemetery at Newville Baptist Church in Newville, Alabama.